A back-of-envelope calculation can give some idea.

If the Deccan Plate moved through some 60░ of latitude during its rapid Mesozoic rafting from Antarctica to itsá position at the K/T boundary it will have traversed almost 7,000 km from say 100 Ma to 65 Ma. Reports on the recent tsunami suggest that it was generated by an 11 m slip along a 1200 km boundary. Averaging out 10 m slips over the 35 Ma between 100 Ma and 65 Ma would give movement capable of generating tsunami of similar size every 50 years. Movement of the Deccan Plate over the past 65 Ma has been significantly slower and it has travelled a further 4,500 km. This would average 450,000 ten metre slips in the past 65 Ma or one slip every 150 years. However, tectonic plates are not entirely rigid and do not move en masse and movements are likely to be clustered rather than evenly spread. It seems inevitable that the relative movements between the Asian and Deccan Plates would have progressively reduced since the Deccan and Asian contact and the distribution of magnitude and frequency would be nothing like this averaging out, but it does give some indication of the potential importance of tsunami as an evolutionary selective force on coastal biotas.

Although there was little awareness of tsunami threats in Sri Lanka before 26th December 2004, there are literary references in mediaeval Sinhalese texts to tidal flooding decimating the coastline and settlements. The coastline from Kelaniya to Mannar on the west coast was affected during one flooding event in the 2nd Century AD.

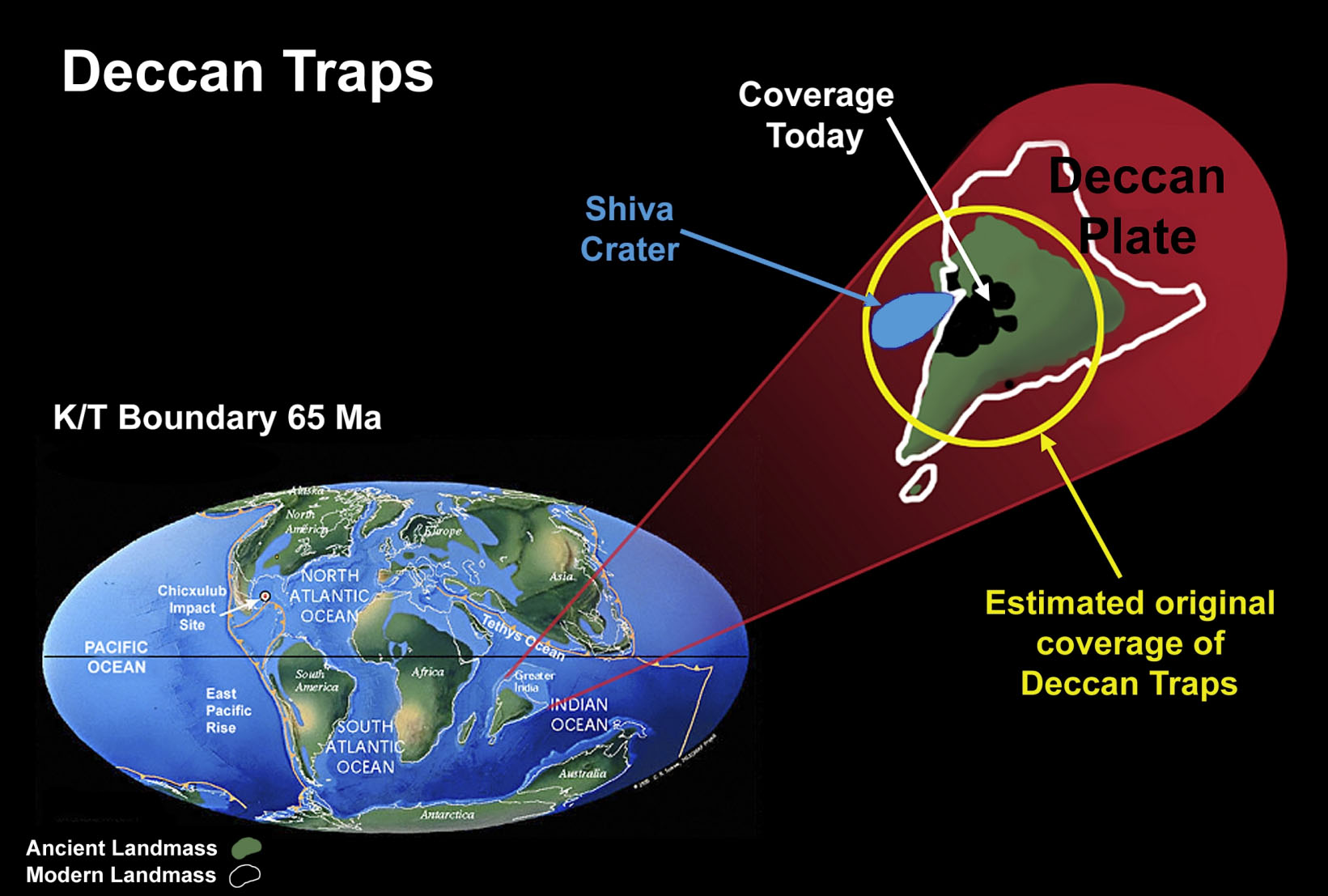

To understand current tectonic events and the historical origins of Sri Lanka's snail fauna requires a step back in time to the Mesozoic origins of the Deccan or Indian tectonic plate. Palaeomagnetic records support a history of the Deccan Plate in which it separated from the southern continent of Gondwana at about 130Ma and, after breaking away from Madagascar around 90Ma, rafted across the Tethys Ocean to make land contact with Asia at about 30Ma. The ongoing collision of the Deccan and Eurasian plates has been described as the most profound tectonic event in the past 100Ma. The leading submarine plate margin may have made contact with Asia at the 65Ma K/T boundary and one current hypothesis is that the massive energy generated by this collision of continents could have given rise to the devastating volcanism and lava flows that formed the Deccan Traps. Although the Chicxulub meteorite impact has dominated explanations for the K/T extinctions for the past few decades, a strong case remains for arguing that the Deccan Traps were primarily responsible for K/T extinctions.

As the southernmost part of the Mesozoic island Deccan Plate it could be that the land area currently composing Sri Lanka was part of a refuge from the devastating impact of the trap lava as it flowed across most of the Deccan Plate land mass. In fact coastal margin reconstructions for the K/T boundary show a much smaller, more isolated island on an area currently occupied by a part of southern Sri Lanka. The Gondwanan fauna in contact with the traps would have been obliterated and, when land contact was made with Asia, recolonisation across the traps would have been in competition with a northern fauna. This may be why Sri Lanka has several snail groups thought to have ancient origins in Gondwana that are poorly represented in or completely absent from India. This scenario is complicated by evidence that other fragments of Gondwana may have been assimilated into the Deccan Plate during its rapid movement north but the timing for this is not clear. An additional complication from the European Mesozoic fossil record is that our supposed Gondwanan taxa appear to have been part of what was a Pangaean fauna. We have some considerable way to go before South Asian faunal origins are unraveled.

Sri Lanka is an integral part of the Deccan Plate currently separated from India by the shallow and narrow Palk Straits. It has repeatedly been connected to the mainland, most recently about 10,000 years ago. More significant than the current sea channel in isolating and shaping Sri Lanka's distinctive, highly diverse and endemic land snail fauna has probably been the fact that the rainforests in the south-west of the island are isolated from the seasonal rainforests of India's Western Ghats. This climate pattern with extensive arid zones in northern Sri Lanka and southern India appears to have a longer history than Sri Lanka's current island state.

Deccan Trap flows and early formation of the Himalaya possibly represented the peak of post-collision tectonic activity. However, fossil evidence indicates that, among other effects, major tectonic events during rafting of the Deccan Plate generated massive flooding that washed terrestrial species out to sea. Thus massive inundation of the sea onto coastal areas of the Deccan Plate predated Asian contact and, as we have just been made brutally aware, such flooding is not confined to the distant past.

The land area of what is now Sri Lanka was much smaller

at 65 Ma and it was further from the continental landmass at the

time that it could have acted as a biotic refuge from the Deccan

Trap lava flows. Details of the complexity and extent of landform and orogenic

activity between the Deccan Plate and Asia are largely unknown and

no attempt has been made to include them in this figure. Estimates

suggest that crustal shortening of the northern leading edge of

the Deccan Plate following contact with the Eurasian Plate was in

the order of 1,500 km. There is evidence that the Tibetan area was

a separate continental plate that had earlier fused with Asia. Further

evidence suggests that several additional island plate fragments,

possibly of Gondwanan origin, had fused with the Deccan Plate during

its northern passage, a movement that was at a far greater rate

than any current plate movements. The massive subduction of ocean

floor between the Deccan and Eurasian Plates and the associated

volcanic and orogenic activity was replaced as a mechanism for mountain

building by compression between the two plates only from the end

of the Mesozoic. The lateral displacement of plates through over

100 Ma would have generated numerous tsunami of enormous magnitude

that seem likely to have been sufficiently frequent to act as a

powerful selective force on the evolution of coastal biotas.

The land area of what is now Sri Lanka was much smaller

at 65 Ma and it was further from the continental landmass at the

time that it could have acted as a biotic refuge from the Deccan

Trap lava flows. Details of the complexity and extent of landform and orogenic

activity between the Deccan Plate and Asia are largely unknown and

no attempt has been made to include them in this figure. Estimates

suggest that crustal shortening of the northern leading edge of

the Deccan Plate following contact with the Eurasian Plate was in

the order of 1,500 km. There is evidence that the Tibetan area was

a separate continental plate that had earlier fused with Asia. Further

evidence suggests that several additional island plate fragments,

possibly of Gondwanan origin, had fused with the Deccan Plate during

its northern passage, a movement that was at a far greater rate

than any current plate movements. The massive subduction of ocean

floor between the Deccan and Eurasian Plates and the associated

volcanic and orogenic activity was replaced as a mechanism for mountain

building by compression between the two plates only from the end

of the Mesozoic. The lateral displacement of plates through over

100 Ma would have generated numerous tsunami of enormous magnitude

that seem likely to have been sufficiently frequent to act as a

powerful selective force on the evolution of coastal biotas.

[Figure reproduced from Naggs & Raheem, in press. Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No 68. World map at K/T boundary from Scotese (2002); Deccan Plate after McLean (1985)].

An idiot's guide to Deccan traps can be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deccan_Traps